History of Tusheti

Origin of Tushs

The origin of the Tusheti inhabitants is still somehow unclear. An amusing legend says that once upon a time, there appeared a pregnant woman on the top of Borbalo Pass. She had been expelled from her native village and thus gave birth to her three sons in this pass, which lies on the border of four historic regions, Kakheti Pankisi Valley, and the mountain regions of Pshavi, Khevsureti, and Tusheti. Each of her sons rolled down the hill to a different valley, i.e. Pshavi, Khevsureti and Tusheti. This is where the locals derive their origin from.

In fact, Tusheti usually served as a refuge for people fleeing from other regions persecuted or escaping from a number of threats (oppression, tax, crime, or blood feud). Local names frequently of Vainakh origin give evidence of the area having been inhabited by the Vainakhs (predecessors of nowadays Chechens and Ingush, related to Dagestani nations) who had better access to the region than the Georgians from Kakheti Valley. The Soviet historiography often depicts Tushs as directly linked to Vainakh (Nakh) tribes, which (supposedly along with the appearance of Christianity) adopted the Georgian culture and language. Only Tsova-Tushs (Bats people) retained their original Bats language. According to certain theories, the actual name of Tusheti and the ethnonym Tushs may refer to the Ingush name Tusholi (goddess of harvest and fertility).

With no regard to any legends, the Tushs represent a mixture of descendants of numerous ethnical and subethnical groups which found shelter in the mountains and formed local villages and Communitys. Acceptance of newcomers in the Community gradually became an important rite, usually a result of a year-long process, held at ritual places most important for the community.

Fragments of ancient and medieval history of Tusheti

The first traces of settlement in Tusheti were dated with certainty to the Bronze Age (12th - 9th century BC). Nonetheless, the region may have been inhabited even a thousand years earlier. Archaeological findings from the Bronze Age are rather scarce accidental discoveries of bronze artefacts. First inhabitants of Tusheti probably settled down in central plateaus of Lower Omalo and Shenako, where findings involve graves and other artefacts from the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age. The region seems to have served as a centre of mineral resources extraction. Some of the mentioned artefacts are exhibited in the Visitor's Centre in Lower Omalo; others may be seen in the ethnographic exposition in Keselo or in the National Museum of Georgia in Tbilisi.

The earliest written mentions of Tusheti come from Greek geographer and historian Ptolemy, who writes about a region where "...between Mount Caucasus and Mount Keraun there live the Tusks (author's note: i.e. Tushs) and Didurebs (author's note: i.e. the Didos - Dagestan nationality neighbouring with the Tushs, parallel ethnonym of the Tsez). Tusheti appears to have been already part of the Kingdom of Kartli (Iberia) founded by King Pharnavaz in the 3rd century BC. Pharnavaz's son Saurmag was Durdzuk after his mother and found temporary shelter with Dzurdzuks during the uprising of Kartli magnates. First penetrations of Georgian ethnic groups in the land of Durdzuks apparently date back to the period of the Kingdom of Kartli. Armenian geography from the 7th century, presumably written by Anania Shirakatsi, also localize Tushs in their current territory. The 8th century in Tusheti was marked with the dominion of Tsuketi eristavs (dukes settled in the area of current north-eastern Azerbaijan). Only partly successful attempts of Christianization were probably made around the 8th-9th century when Tusheti was ruled by dukes of Pankisi (Pankisi Duchy was then part of the independent Kakheti Kingdom). Until the period of formal Christianization Tusheti served as one of the main refuges for pagan highlanders called Mtielni - according to the Georgian Chronicle (Kartlis Tskhovreba) Tusheti was refuge for those fleeing Pshavi and Khevsureti to avoid Christianization. This thesis is supported by a number of analogical names in Tusheti and Khevsureti (e.g. Khakhabo). Pilgrimages of Khevsurs to Tushetian shrines (pre-Christian) were still recorded in the 50's of the 20th century. Certain shrines in Tusheti were actually owned by Khevsurs and the architecture of some towers particularly in Pirikiti Valley also proves the Khevsureti influence. From the 10th century the Tusheti region was formally under control of Kakheti bishops with their pastoral administration based in Alaverdi. Nevertheless, no church as such was built there during the entire period of the Middle Ages.

At the turn of the 14th century, Tamerlane's military campaigns brought the most severe disaster for medieval Tusheti. It was probably the only time in its history when the Keselo castle in today's Omalo was conquered and completely burnt down. The traces of the fire may still be seen in the basements of its towers. Due to the raids the region got partly depopulated. On the other hand, this quickened the process of construction of clan defence towers.

Modern history of Tusheti

From the 16th-17th century, Tusheti was facing raids from Dagestan and Chechnya. In defence, the Tushs got their clan towers built (as was the case of other mountain nations in the Caucasus). Incongruously, these were frequently built by builders from the northern Caucasus. However, the records on these events are of a rather general character relying on secondary sources and often even contradict. Military events thus mainly remained in Tushetian myths and legends. Raids and attacks from both sides were not the only type of contact between the Tushs and Dagestan nations. People from Dagestan used to sell their goods in Omalo and other Tusheti villages while Tusheti livestock and wool had their market in the neighbouring parts of Dagestan. In the 16th century, Christians fleeing from other parts of the northern and southern Caucasus due to Islamization found their refuge in Tusheti. The Georgian Chronicles Kartlis Tskhovreba state: "The name of Christ was forbidden but in the remote mountain regions of Tusheti, Pshavi, and Khevsureti.".

From the 16th century, the Tushs searched their winter home on the other side of the Central Caucasian Ridge. As recorded, King Levan (1520-1574) gave part of the Alvani pastures at the foothills to Tushs, who built the current villages of Kvemo and Zemo Alvani and Laliskuri. "Howbeit, the Pshavs, Khevsurs, and Tushs had not been subdued to the kings of Kakheti before. The king Levan subjugated them not by force but he promised their sheep could graze with no hindrance in Kakheti. Then he sent oblations to the Cross of Lasha in Tianeti [author's note: main Pshavi shrine of Lashari] and from that time, they provided him with army and paid their tax." (Vakhushti Bagrationi: Aghtsera sameposa sakartvelosa [Description of Kingdom of Georgia] - Kartlis Tskhovreba IV, Tbilisi, 1973, p. 573).In the 17th century the Tushs gained their land for ever. The tradition says that as the loyal subjects of the king the Tushs excelled mainly in 1659, when Georgia was seized by the Persian Army ready to displace tens of thousands of people to Persia. Under the leadership of famed Zezva Gaprindauli, the Tushs took part in the fight against the Persians and played a substantial role in the battle of the Bakhtrioni fort, where Georgian insurgents defeated the Persian garrison. Thus, the Persians led by Salim Khan had to retreat temporarily. On the other hand, not only the Tushs searched their refuge hiding from the Persians in the mountains. This was also the case during the raids by Agha Muhammad Khan at the end of the 18th century.

Tushetian legends also reflect other significant

events referring to the heroic character of the Tusheti warriors. When in

1754-1755 Kakheti was invaded by the Avar ally of the Ottoman empire Nursal

Beg, the Tushs successfully attacked their positions and managed to thwart

their plans to join the Dagestan territory with the Ottoman regions by

occupying Georgian mountains and valleys.

However, the Tushs themselves made their living at the expense of the inhabitants of Kakheti. This was one of the reasons why, in 1781, King Erekle II issued a regulation delimiting the rights of the Tushs to pastures to avoid disputes with other Kakhetians: " The Tushs graze their herds in Kakheti. With God's help they grew in numbers and so did their livestock. Let them hence grow further with the help of God. Howbeit, in the villages of Kakheti where they graze their livestock they outrage, steal and rob the temples and commit other malicious acts pestering the other villages. Herein we hence declare the following: The land for their sheep is Lopoti Valley, Alvani, and Pankisi, let them graze their livestock in these three places. The Pshavs claim their right to Pankisi, to which they have none, as the land belongs to the Tushs. Should they need more grazing land in these three areas, let them graze two herds at a time (400 sheep) behind the villages but no more than that at any time. They shall not steal or do any violence. We have sent an order to all villages to only graze two herds at a time. Should they let more sheep graze, this shall bring deserved punishment upon them. Should the Tushs not adhere, they shall be maltreated and slew by the others, and thieves shall be put to the sword. Therefore, let the Tushs know that they shall not graze more than two herds in each of the villages and they shall not do any bad or they shall be treated as we said." (Dedimov: V vysokogoryakh Kavkaza, Moscow, 1931). Yet, still in the half of the 19th century, there used to be mutual attacks between the Tushs and Dagestan highlanders, the Pshavs, or the Kists from the surrounding valleys.

Tusheti and Tushs in the 19th and 20th century

The

first half of the 19th century in Tusheti was significantly marked

with the Great Caucasian War (1834-1859), in which the Tushs, the Pshavs and

the Khevsurs in their majority sided with the Russian Empire against the

Caucasian Imamate. On the other hand, the Tushs had their interest in retaining

the traditional trade and cooperation with their Muslim neighbors, who used to

sell their goods in Tusheti. Simultaneously, the Tushs partly used to cross the

borders driving their herds through the Dido territory. The legates of the Muslim

leader Imam Shalim held their diplomatic negotiations towards alliance of

mountain nations with Shamil. Imam sent repeatedly his armies to Tusheti and

Khevsureti. At the end of 1836, the army under the command of Adlan burnt to

the ground the village of Diklo and besieged Shenako (see the Legend of the Castle of Love on page DOPLNIT). The legends of Tusheti (see the Legend

of the Pharsma Tower) also mention the unsuccessful raid of Murtaza Khan

between 1841 and 1842. In the 40's and 50's of the 19th century,

i.e. at the time of the culminating Caucasian War, Tusheti villages were

attacked and burnt down several times - particularly Diklo and Shenako (1846),

Pirikiti Valley (1848), and Chaghma Tusheti (1850). Tusheti suffered the greatest

aggression in 1852, when all three valleys of Chaghma, Gometsari and Pirikiti

were invaded. Several legendary Tusheti names of that epoch have been

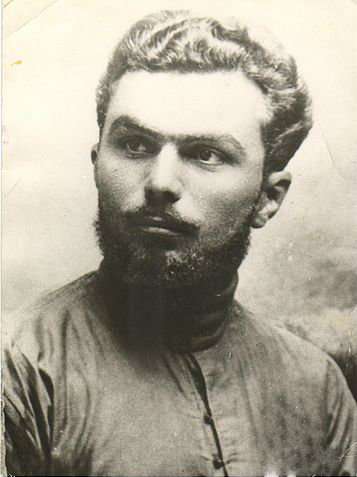

preserved. For example, Shete Gulukhaidze was depicted in the famous portrait by

painter Niko Pirosmanashvili as the hero who took captive Imam Shamil, thus

serving to scare and deter the Avar and other children of highlanders.

At the end of the Caucasian War and stabilization of the region under the Russian

rule, the frequency of raids from Dagestan diminished, apart from occasional

thefts of livestock or horses. Greater military events occurred during the Russo-Turkish

War in 1877, when Ottoman propaganda was spreading along the northern Caucasus

and certain mountain Communitys declared a holy war upon Russia.

In the 19th century, the inhabitants of Tusheti regularly began to migrate to lowlands (temporarily, sometimes even permanently). This also was a result of the Tsar Government policy, which allowed highlanders to gain land at foothills, in fertile Kakheti. Nevertheless, the imminent reasons were natural disasters and epidemics - for example, one village in Tsovata Valley named Sagirta was destroyed by a flood and landslides in 1830. Other villages were hit by plague outbreaks. First villages were depopulated in the westernmost part of Tusheti due to these disasters. The Tsova Tushs came first with the process of dual farming, i.e. summer pastures in the mountains and a winter base in the village of Alvani at the foothills. They were soon followed by other Tushs. At the turn of the 19th century, at least half of the Tusheti population "nomadized" in this manner. This was mainly the task for men since these, under the principles of the Tusheti way of life and social structure, were supposed to graze sheep. The Tusheti dialect hereby adopted new terms, such as Kakhuarebi or Tushuraebi (i.e. people who ascend for winter to the Kakheti lowlands and those who remain in Tusheti, respectively). In the restless period (last at the time of the ruling Mensheviks between 1918 and 1921) of growing raids of Kists to Tusheti (and vice versa), a number of villages remained abandoned all year long (as was the case in the most distant parts of Tusheti - Chontio, Dakiurta, and partly Girevi).

Apparently the most significant interference in the lives of Tushs, their traditions and dual farming split between the lowlands of Kakheti and the mountains of Tusheti, came at the turn of the 40's of the 20th century. This period was characterized by propaganda emphasizing advantageous life in the lowlands and hard life in the mountains. It said that dual farming obstructed the development of life in Tusheti. The real aim was to acquire total control of the mountain nations and the Caucasus. The people were forced to abandon their homes in the mountains and get accustomed to living in the lowlands all year long. The Georgian Soviet Government established agrarian colonies "with prospects" while people from regions "with no prospects" (i.e. also from Tusheti) were supposed to help industrialize the country. Thus, most villages in the mountains were depopulated, the houses dilapidated, and pastures abandoned and not grazed any more.

In the 50's, the inhabitants of Tusheti were forcibly expelled to the lowlands and a "standardized" village was established in Alvani. Omalo and other mountain villages were classified as "with no prospects" for future life and were supposed to be deserted. Although the basic infrastructure (such as schools, medical center, or pharmacy) remained untouched, the people resigned to provide for any maintenance and proper supplies. At the end of the 50's, the school was closed down for pupils whose parents had permanent residency (propiska) in the lowlands. Despite the above-mentioned, people still used to return to Tusheti in the 1960s, at least during religious holidays. It was when unofficial organizers of these events (called shultas in the local dialect) were annually appointed again. Yet, until the 1970s the traditional Tusheti customs were on decline; the new generation did not know the life in the mountains as it used to be, with all its peculiarities, traditions, and rites. People forgot about the clan-based division of land, the differences between fields, meadows and pastures blurred. Moving sheep breeding to Kakheti also caused an ecological disaster for the lowlands that lacked rainwater supplies. The grazed slopes on the Kakheti side of the mountains were more affected by landslides. Moreover, the life in the lowlands and a more intensive interaction with other inhabitants of Kakheti led to the adoption of the local traditions. On the other hand, the ancient Tusheti dialect has been preserved, along with the peculiarities of the religion and the shrines, thanks to the annual rites held in Kakheti and Tusheti alone.

The Georgian Soviet Government showed its interest in resettlement in the mountain areas of the Caucasus at the turn of the 1960s and, little by little, the people were returning to Tusheti. In the 1960s, it was not illegal any more to leave for the mountains and take part in religious festivals and perform rites. The process of resettlement in Tusheti was popularly depicted in the cult Soviet movie Mimino (i.e. "Falcon", 1977), which, however, contains a number of inaccurate ethnographic facts. The feature documentary Shepherd of Tusheti (Tushi Metskhvare, 1976) is more authentic, starring non-professional actors - shepherds. Appointment of Eduard Shevardnadze as the First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party in 1972 became a symbol of Tusheti renaissance. He frequently visited Tusheti and supported the construction of the road that finally connected Omalo and Kakheti for motorized transport in 1981. In the 1980s, there was a library in Omalo, as well as a medical center provided with air medical services, a telegraph station (a remarkable landmark dominating Lower Omalo), and a nursery school. Tusheti was electrified at the end of the 1980s. A project of a new boarding school was launched but never completed due to the collapse of the Soviet Union and due to its proximity to the sacred Tsasne forest at the access road to Omalo. As a foothold for the army in the heart of the Caucasus, Tusheti had a potentially strategic character for both the Georgian and the Soviet Government.

Post-Soviet Tusheti

The fall of the Soviet Union represented another blow to the region. Until then relatively generous subsidies for Tusheti were discontinued, along with electricity supplies, road maintenance, or veterinary services in farming. Successively, the schools were closed down (the last pupil left in 2006), the medical center was canceled, the telegraph and helicopters died away, the state and collective farms were dissolved, the trade ceased, and the people were not given their pay any more. The existing economic system of local wool supplies mainly to the Soviet Army collapsed. The shepherds lost their traditional grazing land in Azerbaijan and Russian Dagestan. Upon the election of President Zviad Gamsakhurdia, when Georgia was passing through the period of its actual non-existence as a state, the inhabitants of Tusheti and Alvani formed units of home defense protecting local communities against predatory raids of field commanders from the remaining territory of Georgia. The situation further aggravated with the war in neighboring Chechnya. Russian aircrafts violated Georgian air space over Tusheti and in some parts interceptors and bombers dropped excessive ammunition. A considerably significant event was the establishment of a monitoring point in Tusheti by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. The mission succeeded in conducting several humanitarian and development projects in the region and providing for occasional helicopter connection with Kakheti. In 2006, however, the village council in Omalo was canceled within the process of centralization in Georgia. The council had served as a self-governing body of Tusheti and maintained a sporadic unofficial contact with its neighbors in Dagestan. Both formally and informally it strived to sustain Tushetian traditions, negotiate with state bodies, and maintain contact with traditional partners in the Northern Caucasus. Nevertheless, within the administrative reform in Georgia, all the respective powers were delegated to the Municipality of Akhmeta, where Tushs are negligibly represented. The crisis of relationships with Russia after 2003 (in particular following the expulsion of Russian spies from Georgia in 2006) entirely eliminated the hitherto existing off-the-record contact between Tusheti and Dagestan. In 2008, many Tusheti men participated in the war in South Ossetia (Giorgi Antsukhelidze being one of the heroes of modern history). Importantly, the head of the Georgian Orthodox Church Ilia II visited Tusheti in 2010 in order to support the influence of the Church in the mountain regions. It is estimated that approximately 12,000 people professed their Tush identity in 2013 (Mühlfried, Florian: op. cit., p. 34).

Old Tushetian traditions have largely been forgotten, though, and a return to Tusheti and its old and often dilapidated houses was rather a return to a weekend house than anything else. Only the beginning of the 21st century saw first attempts of a systemic approach to the development of tourism. The national park was designated and, with the support of generous grants from abroad (and initiative of several local inhabitants), some of the historic monuments were reconstructed, above all the old clan towers Keselo in Omalo. With the help of partners from the USA, the national park was furnished and a large tourist information center was established. Since the end of the first decade of the new millennium, Tusheti has been experiencing a significant growth in tourism, having welcomed about 16000 of official visitors in 2019 (plus estimated 3-4 thousand unregistered visitors).